Meet Us at Here

A practice in homework

Hello there. Hello there with your aliveness and numbness. With your anxiety and answers. With your beauty and body odor.

I know. I’m probably not supposed to write like this(?). But here we are and I’m really not writing to write right I’m writing to connect. Because even though I write this in my time and you read this in your time, perhaps something velvety and soft inhabits the space between you and me. Maybe not. I don’t actually know with words.

I do know if you were really in my kitchen with me right now, I’d probably ask you to hold a baby or two while I get some tea or sit you down to feed you or gossip about something silly.

So, this medium works. It works for what we need to do together right here, wherever here is for you. It’s a practice in homework.

It starts with you, then gets bigger to the land you find your body on and ends with the creation of a whole world. Oh gosh it’s a vulnerable thing to do, so thank you for getting this far with me.

You in your body. You in your mind. You in both on land that can hold it all.

Part 1

We begin outside. Can you find a naked patch of earth? Can you touch it with a naked part of your body like your hands or feet or whatever part of you feels receptive? Can you take 5 slow breaths with the part of you touching earth? Feeding breath to ground and being fed in return. That’s all that’s required and it’s not even really required. Play around with this prompt, no bad answers only good questions.

Part 2

Do you know how the notion of private property was birthed under the U.S. legal system? It was through something called a land patent1, a birth certificate of sorts. A clerical and administrative proceeding built on broken treaties, a speculative secondary market for land and legislative act after legislative act2 that endorsed a certain type of agrarian and capitalistic future. Though there are exceptions, many of the pathways for land patents were effectively ended by the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA) of 1976, which stopped the majority of public‑land disposals.3

There are three main categories to trace land patents:

A Very General Breakdown of the U.S. Land-Patent System

Public-Land States are derived from lands to which the federal government claimed title. Federal land patents apply in the following states: Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Florida, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Dakota, Utah, Washington, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

State-Land States are derived from lands over which certain colonies or states claimed original sovereign title. Land patents in these states are issued by the state rather than the federal government and include Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Hawaii, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Vermont, Virginia, and West Virginia.

Mixed / Special Cases include Alaska, Hawaii, and Texas. Alaska is generally considered part of the public-land states, while Hawaii aligns more closely with state-land states; however, both states are inherently more complex due to current corporate interests and their histories as more modern colonies. Texas retained control of its public lands after annexation and operates its own land-grant system through the Texas General Land Office.

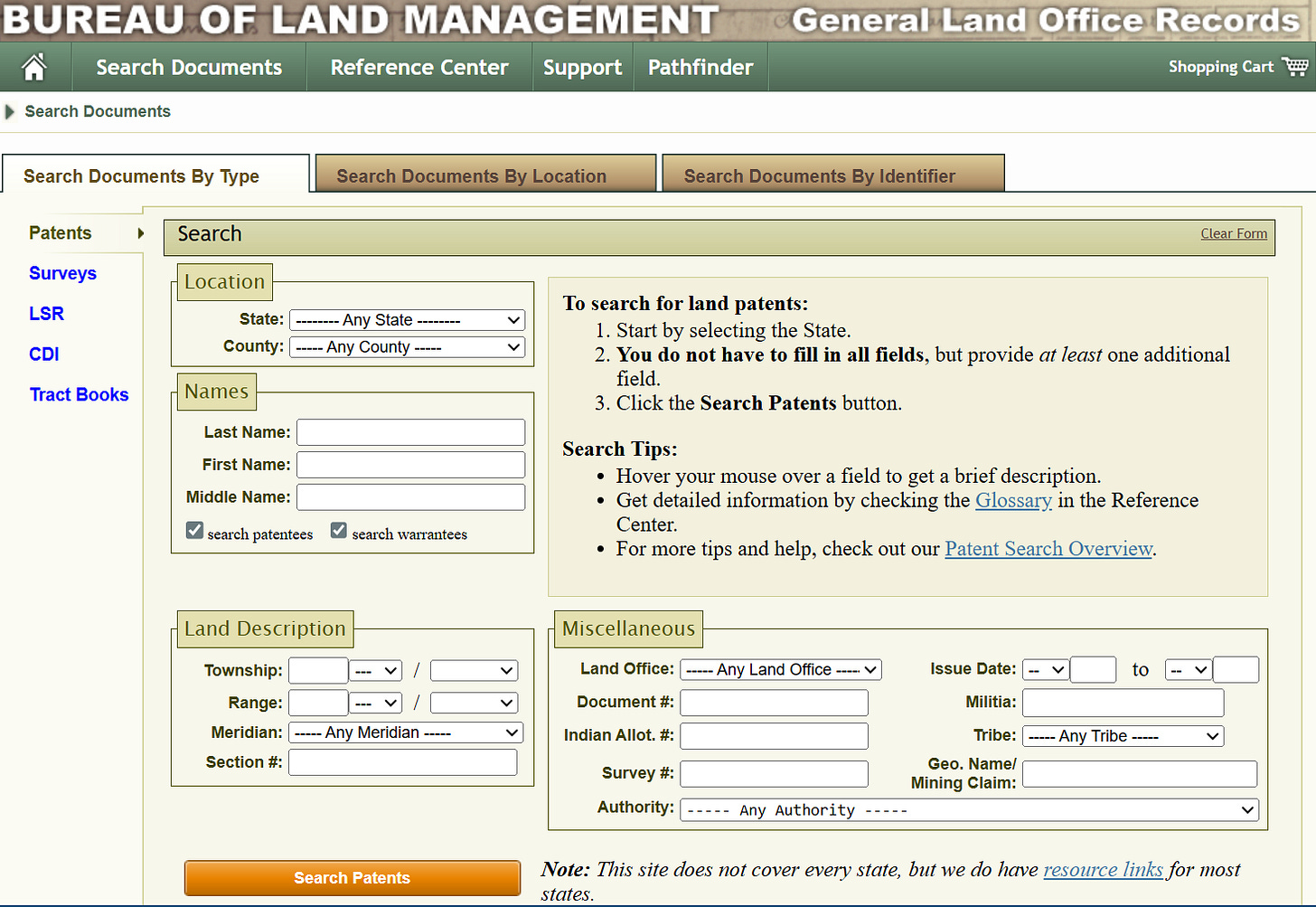

And now, part 2 of the homework, we trace your land here at the Bureau of Land Management General Land Office Records, or GLO. Importantly, GLO only houses the public-land state patents but does have resource links to trace patents in state-land states.4

Either way, the main information we’ll need to trace the patent for the land you call home is the land description. You can use this resource to find that Public Land Survey System (PLSS) description. Simply type in your address to find the relevant Township, Range, Merdian and Section Number. Once you have this information, you can go back to GLO and fill in.

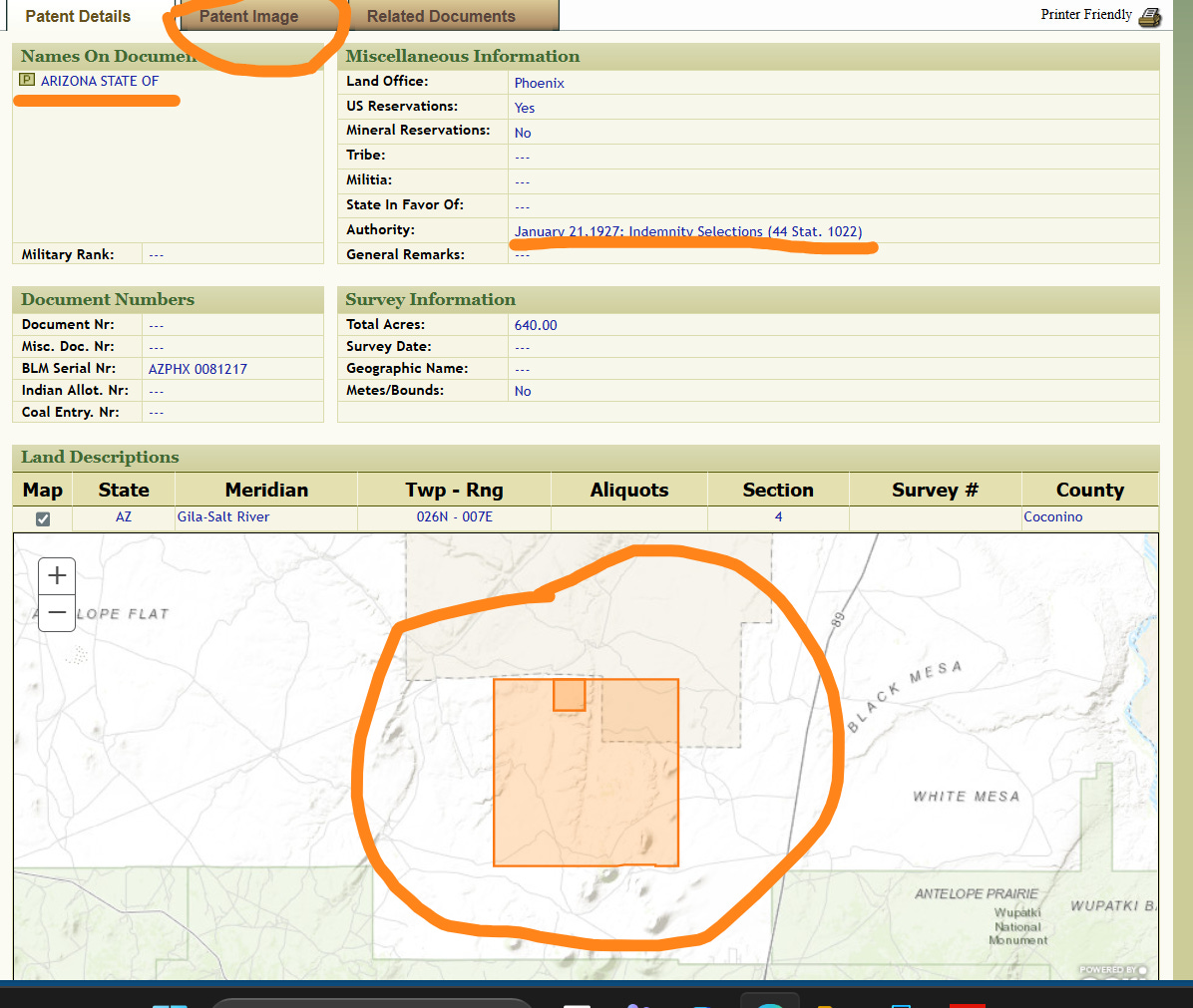

Afterwards, you’ll be prompted to a screen where you can see the names of the patentees, the legislation that enabled the land transfer and even a map of the transferred land as well as an image of the patent.

Allow this to sink in gradually. You might notice the names of real people whose legacy you may have inadvertently stepped into, and that can bring up many feelings. It is a lot, and you’re allowed to move through it with care.

Part 3

We are surrounded by creation stories, even when we don’t realize it. These stories are often embedded in the landscape, pointing toward the beings, animate forces, and relationships we’re meant to pay attention to. The story I think of for the land I live on involves a waterfall, a blue jay, and a moon baby who turns moon man.5

What’s important about these stories is that they move through us, but unless we have been given explicit permission, we are not their keepers and they are not ours to tell. It can be difficult to quiet the modern impulse inside us that wants to narrate and claim, but there is such profound relief in remembering that we are simply invited witness. We get to settle into being part of the story rather than possessing it.

So, this is your Part 3: seek out the creation story/stories of the land where you live that have been shared publicly with permission in a culturally appropriate way. If you can hear it orally, wonderful; if not, look for direct translations in an archive or in an old book. Sit with the story. Visit the places it names. Hold it alongside the land patent and understand that you live inside both realities at once. One is a present legal story of ownership; the other is a deeper story of relation. Please remember, you belong to the latter long before the former belongs to you.

Some fun etymology: the word for patent comes from the Latin word patere, or to lay open. Yes, let’s lay it all open.

The following list is not exhaustive: Land Ordinance of 1785, Northwest Ordinance of 1787, Act Creating the General Land Office (1812), Preemption Act of 1841, Homestead Act of 1862, Southern Homestead Act of 1866, Timber Culture Act of 1873, Desert Land Act of 1877, General Allotment (Dawes) Act of 1887, Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA) of 1976, General Mining Act of 1872, Placer Mining Act (1870 amendments), Coal Lands Act of 1873, Timber and Stone Act of 1878, Stock-Raising Homestead Act of 1916, Mineral Leasing Act of 1920, Pacific Railway Acts (1862, 1864), Swamp Land Act (1849, 1850), Wagon Road Acts, Canal Acts, Military Bounty Land Acts (1776–1855), Indian Homestead Act of 1875, Burke Act of 1906, Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, Alaska Native Allotment Act of 1906, Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) of 1971, Texas Annexation Resolution (1845), Texas empresario grants, Texas headright grants, Texas scrip acts, Texas bounty and donation land acts, Texas railroad land-grant programs, Texas veterans’ land programs, Great Māhele (1848), Kuleana Act (1850), Organic Act of Hawaii (1900), Alaska Statehood Act (1958), Treaty of Paris (1783), Louisiana Purchase Treaty (1803), Adams–Onís Treaty (1819), Oregon Treaty (1846), Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848), Gadsden Purchase (1853), Townsite Acts (1867, 1891, others), Isolated Tracts Acts (1912, 1939), Recreation and Public Purposes Act (1926, 1954), National Industrial Recovery Act (1933).

For what this could mean under the current administration check out this: Secretary of the Interior’s Federal Land Withdrawal Authority Under the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA).

Side note: state-land state descriptions can actually be a lot dreamier, invoking a rock, tree or river as the boundary maker rather than a coordinate system.

Thank you, Snuqualmi Charlie for your story as compiled in Mythology Of Southern Puget Sound: Legends Shared By Tribal Elders.

What a perfect approach, holding these stories alongside each other.