My daughter recently made a new friend on our morning walks, a polypore mushroom. I hadn’t noticed her friend and couldn’t figure out why she was drawn to a corner of the woods off our path but she was insistent. When close enough, she sat down next to polypore and said hi then bye and we were on our way.

I know this story is banal and familiar to many caregivers of young children. The mundane magic of a developing mind; however, her recognition of sentient beings beyond human is more than poetic, it’s felt. Her worldview is animated. She constantly reminds me to feel (not think*) into all the ways I touch the sentient and the sentient touches me. 1

Animacy doesn’t have a single definition and is very much based on the culture composed in. In Latin, the root of the word (anima) translates to life, breath, spirit or soul. I think about animacy as the way everything expresses some form of inhalation and exhalation, how everything at all moments is living, dying or being reborn in loops. It often has found expression in earth-based traditions and folklore tied to place. It doesn’t have to be the same thing as anthropomorphizing because it recognizes and differentiates the experience of each being. 2 In intact cultures of Original People, this is perhaps an understood lifeway; for those of us severed from our place-based traditions of origin, animacy is the universal hum3 we are trying to find again.

For the sake of this essay, I very much reduce the wonder-filled landscape of animacy by bringing in the legal fiction of personhood. Abridged, legal personhood essentially is a being “for the whom the law recognizes to have certain rights or duties.”4 It is the top-down acknowledgment that allows for active participation in society rather than the passive role of “objectified beings” like children, animals, plants, fungi, water and land.

For most of the United States’ recent history, personhood has meant the adult human (note for the greater half of that history that human is likely cis-male, property-holding and white). Throughout the decades, personhood has evolved5 with the most contemporary developments including more-than-human beings as persons, distilled in what is formally known as the Rights of Nature (“RoN”) movement.

I’ll be honest, rights frameworks in isolation taste hollow. I focused my legal education on international human rights and walked away feeling a little empty in the application of the various doctrines and treatises. This weariness extended to the RoN when first introduced to me a couple years ago. Since then I’ve kept a pleasant distance from it, unsure how to hold something as slippery as “moral guarantees.”6 To me, individuated rights (whether for forest or human being) can suck the relationality out of a situation.7

“Eagles build their houses in trees; people call them eagle nests because in the eyes of human beings it is a nest. To the eagles it is a house and home.”

- John Jackson, Haa Atxaayi Haa Kusteeyix Sitee

Recent conversations have led me to investigate my hesitation to play with these legal tools. One of our current projects is with a member of Land Clinic’s advisory council, Wanda Culp. Wanda is many wonderful things.8 Her warmth and honesty bring me so much joy whenever we meet (just thinking about her actually makes me smile big). She is Tlingit, specifically from the Brown Bear (Chookeneidí) clan. We are working on a mapping project examining land claims in Southeast Alaska. During the process, Wanda has sent me many books and art as research guides, including a collection of oral histories. These interviews with Elders in Tlingit bring the practical aspects of what has been deemed “subsistence living” in union with the stories of the many beings that animate the landscapes of Southeast Alaska.

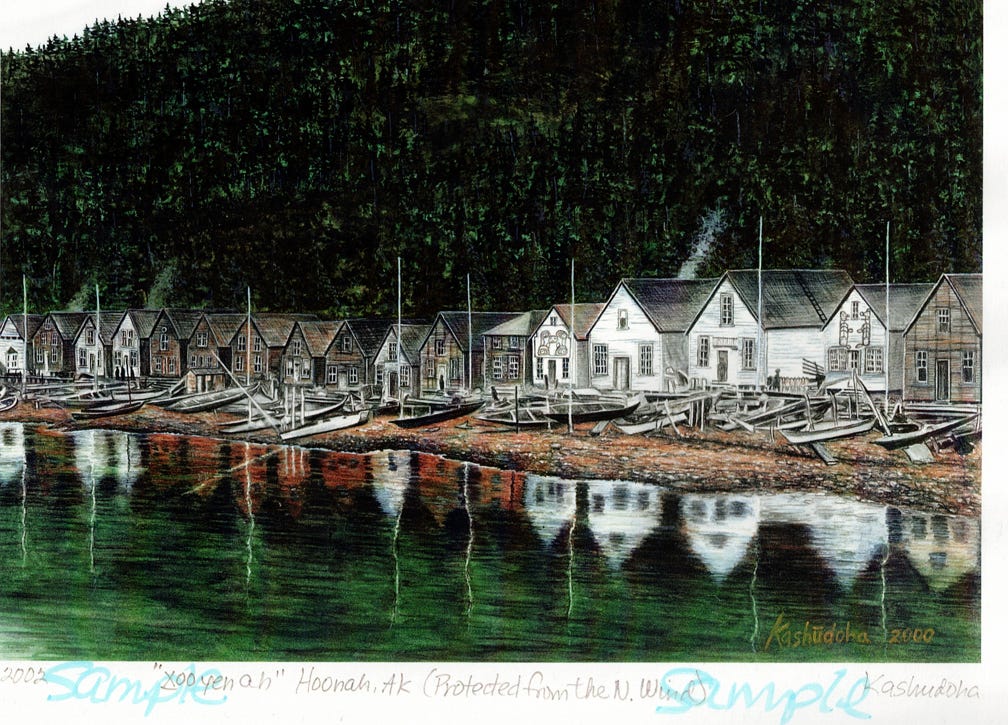

Wanda’s art of “Xooyenah” Hoonah waterfront clan houses before the Hoonah fire of 1944. The fire was caused by jet fuel from an overturned WWII barge.

It would feel incomplete to not include the spirit of these stories in our project, leading us down a path that feels miry and creative. We are learning the contours of what is appropriate to share (including what is appropriate to share with me) and what is absolutely necessary to share to adequately reflect the thefts and loss caused by colonization. We are incorporating Wanda’s art as foundation. We are dancing in a space that many don’t understand because we are not necessarily looking for solutions, we are recovering what the United States has invisibilized.

To aid us, my mentorship with Creature Conserve9 starts this month. Creature Conserve is “[a] support system for artists, writers, and scientists as they collaborate and explore the human connection to nature, creating new pathways to a healthier world for all creatures.” I’m really not sure the outcomes of any of this but I’m excited to share our process out as it develops.

In returning to my question (how do we hold a hum), the answer that seems to arrive for me is we don’t. Just as land holds us and we don’t hold the land, the hum holds us we don’t hold the hum. We just need to listen.

Parting gift: A playlist to play with animacy. May the reverb produce echoes of that universal hum.

Elements of animacy can be found in many cultures:

“The concept of àṣẹ (pronounced \’ahh-,shay\) in Yoruba philosophy and cosmology, which has spread via Afro-diasporic manifestations of the Ifá spiritual tradition (Candomblé, Haitian Vodou, Santería, Lucumí, etc.,), promotes the idea that a spiritual and generative force inhabits every being, animate or inanimate.”

“Slavic languages have a somewhat complex hierarchy of animacy in which syntactically animate nouns may include both humans and more-than-human beings/experiences like mushrooms and dances.”

“The adoption of Catholic saints as animate forces of culture. Folk Catholicism can be broadly described as various ethnic expressions and practices of Catholicism intermingled with aspects of folk religion.”

“Marriages between humans and non-humans (irui konin tan (異類婚姻譚, "tales of heterotype marriages") comprise a major category or motif in Japanese folklore.”

Robin Wall Kimmer has told us that in Potawatomi rocks are animate, as are mountains and water and fire and places.

“The earliest Hebrew religion was animistic, that is, the Hebrews seemed worship forces of nature that dwelled in the natural world. As a result, much of early Hebrew religion had a number of practices that fall into the category of magic.”

“And what I mean, when I talk about the personhood of all beings, plants included, is not that I am attributing human characteristics to them — not at all. I’m attributing plant characteristics to plants. Just as it would be disrespectful to try and put plants in the same category, through the lens of anthropomorphism, I think it’s also deeply disrespectful to say that they have no consciousness, no awareness, no being-ness at all. And this denial of personhood to all other beings is increasingly being refuted by science itself.” Robin Wall Kimmer, The Intelligence of Plants.

I heard animacy described as a hum on The Emerald Podcast and thought it was so apt. Thank you Julia Mande for the podcast recommendation.

Montes Franceschini M. Traditional Conceptions of the Legal Person and Nonhuman Animals. (Basel). 2022 Sep 28;12(19):2590. doi: 10.3390/ani12192590. PMID: 36230329; PMCID: PMC9558555.

Craig M. Kauffman and Pamela L. Martin. The Politics of Rights of Nature: Strategies for Building a More Sustainable Future. MIT Press (2023).

The Internet Enclycopedia of Philosophy, Human Rights. https://iep.utm.edu/hum-rts/.

For example, the broad statement of a forest owning itself sits funny with me. It obscures the interactions of human beings with place and imports concepts of ownership that I think the overculture needs to revisit. With that said, I understand how RoN has been a critical tool for tribal governments and community organizations to support their lifeways and ecosystems. I also understand the need to use the language of the courts as a bridge to something more, I guess I’m really just interested in that something more.

Wanda is a mother, grandmother, as well as a Tlingit activist and advocate, born and raised in Juneau and Hoonah, Alaska. An artist by trade, Wanda is also a hunter, fisherwoman, and gatherer of wild foods.

Thank you Betsy MacWhinney for sharing mentorship program with me.

"We are dancing in a space that many don’t understand because we are not necessarily looking for solutions, we are recovering what the United States has invisibilized." This post really resonated. Thank you for putting into words much of what I struggle with myself.

Mesmerizing and informative. Thank you.