Hesat is an incarnation of the Egyptian goddess Hathor. The Temple of Hathor at Serabit el-Khadim is one of the birthplace of the modern Latin alphabet. Underneath her is the Proto-Sinaitic letter for A (Aleph). Image Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hathor

Ours is a time shaped by text and the subjective interpretations that follow.1 The written word is a powerful tool that often dictates how we relate to one another and engage in meaning-making. For a long time, I was troubled by this — considering how much words composed in isolation have supplanted oral traditions and cultures. However, recently, I’ve come to appreciate all that these lines can bring.2

When we peel back words, we find letters or characters that represent whole worlds within themselves. I suspect for most of human existence we have used images and symbols, reaching across linear time, to mark occasion, honor gods and find each other. 3

This symbolic impulse stretches far back into human history. Estimated to be between 75,000 and 100,000 years old, this cross-hatched ochre piece from Blombos Cave, South Africa is one of the earliest known examples of symbology by homo sapiens.

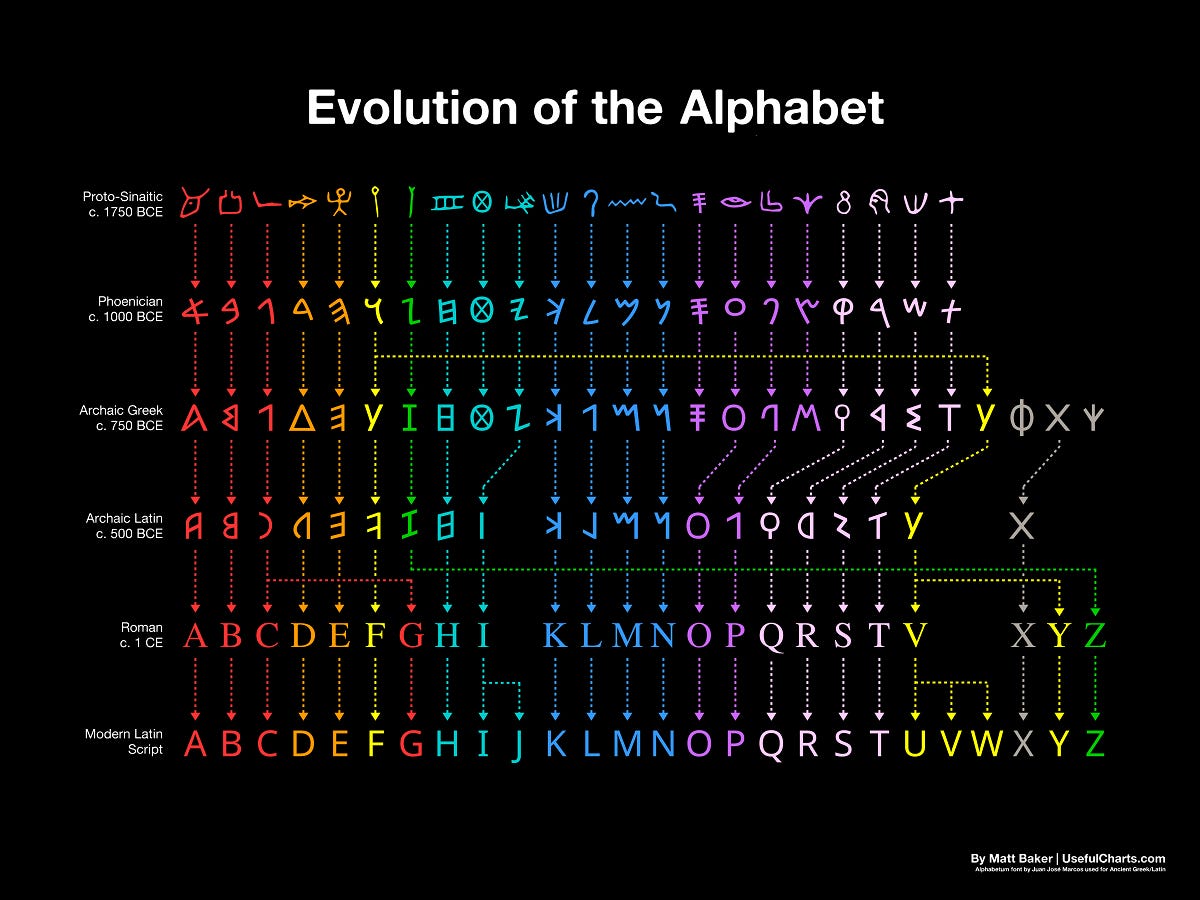

Even our modern Latin alphabet has origins in the sacred.4 This is the alphabet I (and maybe you because you are reading this) work with every day. It is a descendant of Proto-Sinaitic script, one of the first alphabetic writing systems we have a collective memory of. It is most likely a derivative itself from Egyptian Hieroglyphs and Babylonian cuneiform.5 It is an ancestor to Phoenician, Hebrew, Arabic, Greek, Etruscan, Roman, and of course, the very letters I type now.

Source: https://usefulcharts.com/blogs/charts/evolution-of-the-english-alphabet

Many scholars believe that for most of the alphabet’s history, it was read out loud and paired with physical gestures to relay the full impact of meaning.6 Early proto-writing and symbols from all around the world were and still are integrated with ritual, music, movement, or carving.7 An additional practice called subvocalization (muttering or whispering the words while reading) was the norm in Western cultures until around the 10th century CE.8 The idea of reading as a spoken, embodied act challenges our modern idea of silent, disembodied text.

The Natural Language of the Hand (1644)

This long tradition of reading as a physical, spoken act reminds us that the meaning of words has always been shaped by context, performance, and shared understanding. This is reflected in a body of critical legal scholarship that challenges conventional contract law by exposing how contracts often mask power imbalances and serve dominant economic interests. Rather than rejecting contracts altogether, these scholars envision a contract law grounded in fairness and relational accountability. They advocate using contracts not just as tools of market exchange, but as potential instruments of solidarity, resistance, and more equitable relationships.9

Here at the clinic, we’re often asked at what point something becomes “legally binding.” For how sophisticated contracts have become, their foundation is simple and require 4 elements:

An Offer

Acceptance

A Reciprocal Exchange

Intention to Create a Relationship

I offer you wood, you accept the wood and provide me shelter in exchange and we both benefit from the sheltered fire we make our food on together. The core of our exchange is a mutually beneficial shared meal. In the eyes of the legal system, this could be a contract but this is also a relationship, this is also survival.

As we explored earlier, the alphabet was not always a tool of abstraction but a vessel for the human and the sacred—used to encode stories, rituals, and wisdom that could only be fully understood through context, memory, and felt knowledge. Meaning lived beyond the marks themselves. As time spirals in all directions and the present world continues to unwind, it feels increasingly important to ask: who is at the center of our memorialized bonds? By naming this, maybe we can inhabit the lineage of the alphabet as both reverent and situated to guide some of all that may come.10

This tension between text and interpretation also runs through constitutional law in the United States, where competing theories shape how meaning is drawn from foundational documents: Textualism focuses on the ordinary meaning of the Constitution’s words at the time they were written, while originalism seeks to uncover either the framers’ intent or the original public understanding at ratification. In contrast, the living Constitution approach treats the document as evolving with contemporary societal values. Structuralism interprets the Constitution based on its overall framework and the relationships it creates between institutions, emphasizing principles like federalism and separation of powers. Doctrinalism relies on judicial precedents and case law to guide consistent interpretation. Ethical reasoning draws from moral and philosophical principles embedded in the Constitution, such as liberty or equality, while historical practice and tradition uses longstanding customs to inform meaning.

This alphabet fixation started after engaging with some of the mythosomatic course work of the Mythic Body.

It doesn’t feel accidental that many ancient texts, symbols and art are found in the womb space of the cave. A spiritual container to hold and center the acoustics of words and ceremony in the many forms.

Sacred text and symbol are not only ancient—they are spatial. Many inscriptions can be found on or near the Temple of Hathor at Serabit el-Khadim in the Sinai Peninsula, a major religious and administrative site associated with Egyptian turquoise mining expeditions during the Middle Kingdom (c. 1900 BCE) and New Kingdom periods. Dedicated to Hathor, the Egyptian goddess of love, music, and mining, the temple served as both a spiritual hub and a cultural meeting point between Egyptians and Semitic-speaking slaves or prisoners who worked in the mines.

Sacks, D. Letter perfect: The marvelous history of our alphabet from A to Z. Broadway Books. (2003).

Sacks, D. Letter perfect: The marvelous history of our alphabet from A to Z. Broadway Books. (2003).

Scarre, Chris & Lawson, Graeme, Archaeoacoustics, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research (2006); Oppitz, Michael, Ritual and Writing in Dongba Culture, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London (2001).

Paul Saenger’s seminal work documents how silent reading only became widespread in the West during the High Middle Ages, particularly after changes in text formatting (e.g., spacing between words) made silent comprehension easier. Before that, reading aloud or subvocally was standard, even in private. Saenger, Paul, Space Between Words: The Origins of Silent Reading. Stanford University Press, 1997.

See Duncan Kennedy, Form and Substance in Private Law Adjudication, 89 Harv. L. Rev. 1685 (1976); Karl Klare, The Public/Private Distinction in Labor Law, 130 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1358 (1982); Margaret Jane Radin, Boilerplate: The Fine Print, Vanishing Rights, and the Rule of Law (2013); Angela Harris, Race and Essentialism in Feminist Legal Theory, 42 Stan. L. Rev. 581 (1990); Devon Carbado & Mitu Gulati, Working Identity, 85 Cornell L. Rev. 1258 (2000); Cheryl I. Harris, Whiteness as Property, 106 Harv. L. Rev. 1707 (1993); Khiara M. Bridges, The Poverty of Privacy Rights (2017); Destin Jenkins, The Bonds of Inequality: Debt and the Making of the American City (2021).

One way we work with this at the clinic is by embedding the land’s story into land exchange documents themselves. This could be an acknolwedgment of an important waterway and the creatures that inhabit the water, a summation of the ways the US government has stolen land underneath the feet of people or naming the power dynamics of the parties as it relates to the land.