The Palouse People, Eminent Domain and the Snake River

The Story of KHIMSTONIK and Her Lineal Descendants

This month we’re featuring one of our clinic client-collaborators, KHIMSTONIK, and the work they are doing in Southeast Washington, specifically lands on the Snake River around the Ice Harbor Dam. If you would like to support the work of the Palouse and KHIMSTONIK, please consider donating directly to the organization.

The Lady Who Does Tasks Quickly

My name is ILL-LAH-WAH-LITZ-TUN-MYE (Lady who does tasks quickly). My English name is Ione IronHorse Martel Jones. I am an enrolled member of the Confederated Tribes and Bands of Yakama Nation and a lineal descendant of the WOW-YICK-MA NAH-KHEE-UM NU-SHWA, the People from Lower Snake River Palouse.

I am also the Executive Director and President of KHIMSTONIK, a tax-exempt Section 501(C)(3) nonprofit organization. Named after my Kuthla (grandmother), KHIMSTONIK seeks to understand the systems affecting Indian Country and to identify the ongoing disparities arising out of centuries of cultural appropriation and land thefts.

My current focus is to continue my family's mission of land return for the hundreds of acres taken by the US Army Corp via eminent domain in 1959.

Keepers of the Past

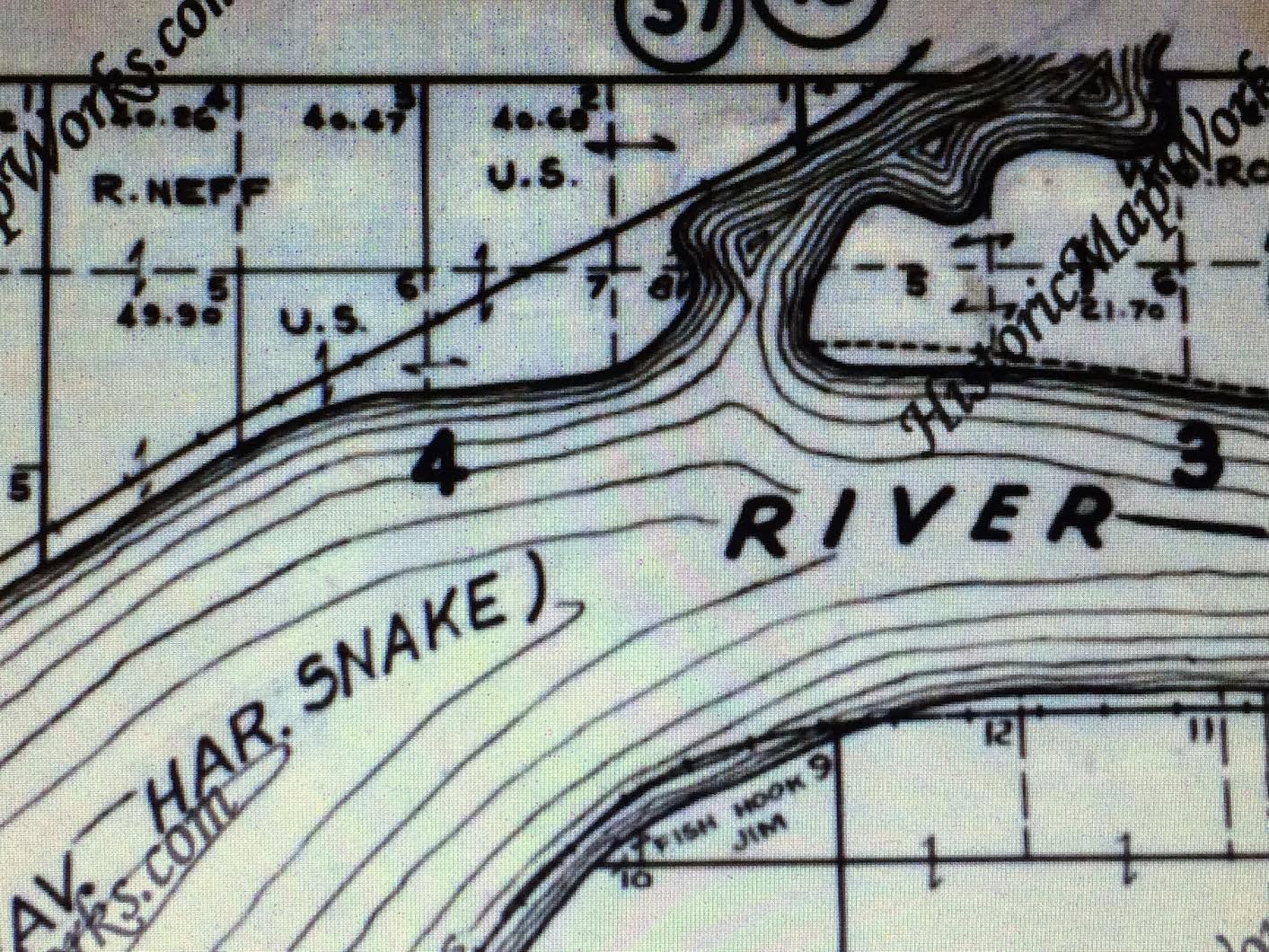

My family descends from WOW-YICK-MA NAH-KHEE-UM NU-SHWA, the People from Lower Snake River Palouse. The Palouse are a distinct band of Ichishkin speaking people located in the confluence of the states of Oregon, Washington and Idaho. My ancestors resisted signing onto the Yakama Treaty of 1855, so our family’s land claims are a bit different from others in the area. My relatives CHO-WAWA-TYET (Indian Jim), XILCH-KO-WAKS WACH-OM-KYE (Wolf Necklace) and AL-LI-LUYA (Thomas Jim) received land patents under the Homestead Act of 1862 that guaranteed title (rather than a trust relationship) to our ancestral lands. Our family remained in the area until 1959 when the US Army Corp instituted a “condemnation” proceeding (eminent domain) and forced us to move off the land.

I am not the first in my family to advocate for our land return. I follow in the footsteps of all my relatives that have held the U.S. government accountable since April 19, 1880. This includes my grandmother, KHIMSTONIK (Mary Jim Chapman). She was there the day that her relatives were taken from their final resting place on Fishhook Island (now under water due to the dam) in preparation for the Ice Harbor Dam.

We have received so many false starts to the return. KHIMSTONIK and my Aunt AYATOOTONMI (Carrie) went so far as to testify in the 1988 U.S. Senate Hearing Before the Select Committee on Indian Affairs before the late Senator Daniel K. Inouye of Hawaii and Senator Daniel J. Evans of Washington. During the meeting, promises regarding our relatives were actually addressed on the record. Though these promises did not lead anywhere, the family never stopped remembering our relatives and the fight for our land.

To read more about my family’s story, including first hand accounts from KHIMSTONIK and AYATOOTONMI, check out this article written in 1993.

What is Eminent Domain?

Eminent domain is the power of a governmental entity to take land for public use without the owner's consent. This power comes from the common law concepts of “necessity and sovereignty” but has been codified (made into a law) by the legislative branch.1

Common law is judge-created law. This means that a judge made an objective decision that turned into the precedent that other judges follow.

A judge looks at the following criteria when determining whether a taking is appropriate:

The taking of the land (also known as condemnation) of the property is reasonably necessary.

The land will be used for a public purpose.

Just compensation is paid to the land owner for the condemned property.

In the case of my family, the judge found that the creation of the dam outweighed our (and others in the surrounding area) claims to our land. For the estimated 18 descendants, the US Army Corp collectively paid out just $3,500 (percentages received at varying rates) for hundreds of acres of our ancestral home.

It’s worth noting that after the construction of the dam, some of the settler families that were subject to the 1959 taking were given an opportunity to return to their land. We’d like the same opportunity afforded to us.

Where is the Land Today?

I have dedicated years of my life to sift through government paperwork and FOIA requests, pursue higher education degrees (I am a professional accountant and real estate broker) and keep the traditions I was taught by my Kuthla. I’ve had my fill of sympathies with no leads and attorneys that have no understanding of the complexities behind these sorts of land transfer. Using my research as the foundation, KHIMSTONIK has partnered with Land Clinic and JD Calkins Law and Consulting PLLC to identify the parcels and reassess the legal standing of the government to do the taking in the first place. We continue to unravel the conflicting paper trails left in the wake of the taking.

Wandering Minds

My family’s story is challenging for a reason, it’s been buried in a system that is intentionally complicated and emotionally draining. This hard place is forcing us to think about other ways to imagine land return. Could there be such a thing as a reversal of eminent domain? Is there a way to collaborate directly with present-day private landowners that are not using the spaces? How can this begin an important precedent for the approximately 740 dams2 that the US Army Corp owns and operates? How are our learnings helpful frameworks for others searching for validation of their own family's experience?

The Ice Harbor Dam is one of the four dams being considered for removal by the state of Washington. This complicates an already complicated process but gives us a lot of hope in terms of the shift in political consciousness that’s arising.

Do you know wak amu?

To close, I’d like to introduce you to wak amu (“hamash” or the great camas flower). Wak amu grows in patches as a tuber. An interesting fact about the great camas is that it actually benefits from wild cultivation. It’s through its wound that the great camas are able to create new offset bulbs. Modern science has documented the large role gophers play in ecosystem development through feasting on the purple flower’s root systems.3

We gather and prepare wak amu bulbs in June. The total cooking process takes two to three days (not including gathering days). Our tradition reflects the ways in which all Original Peoples are meant to have a relationship to their homelands and teach others how to do so as well. Our Palouse culture is endowed with practices that can loosely be translated as sustainability principles. Through observing the way the plants and animals interact with the rivers, mountains, prairies and us (N’TITYTE, the human beings), we can weave together the stories of those who came before us and sustain our landscapes for those future generations yet to come.

See §40 U.S.C. 258a.

https://www.usace.army.mil/Missions/Civil-Works/Dam-Safety-Program/

https://www.wnps.org/native-plant-directory/67-camassia-quamash

Really grateful to be able to read this story and learn about this effort. Thank you. 🧡